- Thu 11 May 2023

- nature

- Gemma Conroy

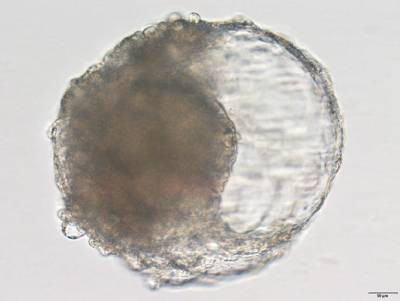

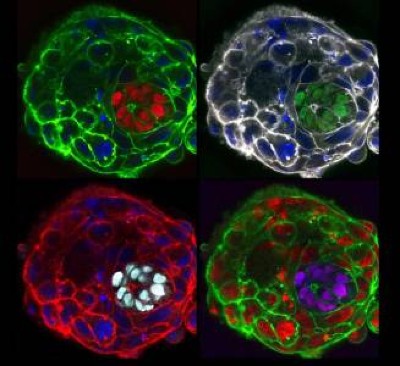

A 25-day-old monkey embryo stained with conventional dye (pink) and with fluorescent dyes (multicoloured). Blue denotes cell nuclei; the dense central patch of green and red marks trophoblasts, cells in the embryo’s outer layer. Credit: Zhai et al./Cell

Scientists have cultivated monkey embryos in the laboratory long enough to watch the beginning of organ formation and the development of the nervous system — milestones that are difficult to observe in embryos growing in the uterus. The embryos reached the age of 25 days, making them what might be the oldest primate embryos to be grown outside the womb.

Independent teams described the findings in separate papers 1 , 2 in Cell on 11 May.

“It’s very impressive,” says Magdalena Zernicka-Goetz, a developmental biologist at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena, who was not involved in the research. “It’s going to bring a lot of new insights.”

Going 3D

Few things are as difficult as keeping lab-grown embryos alive for longer than a couple of weeks — most amount to nothing more than a mixed bag of cells in a dish. Previously, both teams had managed to culture monkey blastocysts — balls of dividing cells — in Petri dishes for up to 20 days 3 , 4 . Past that point, all the embryos had collapsed, making it impossible to see more advanced stages of their development, such as early signs of the nervous system and organ formation.

But in the new studies, the researchers grew monkey embryos in small vials of culture medium, which allowed the embryos to grow in three dimensions as they would inside the womb. Both teams coaxed their embryos to survive for 25 days after fertilization. Neither the authors nor outside scientists contacted by Nature knew of older primate embryos grown in the lab.

Watching organs take shape

Hongmei Wang, a developmental biologist at the State Key Laboratory of Stem Cell and Reproductive Biology at the Chinese Academy of Sciences in Beijing, and her team obtained egg cells from female cynomolgus monkeys ( Macaca fascicularis ) and fertilized them in the lab with sperm collected from their male counterparts. A week later, they placed the resulting blastocysts into a gel-like substance in small cylindrical containers and watched them grow for 25 days.

Stem-cell-derived ‘embryos’ implanted in monkeys

Roughly two weeks after fertilization, more than half of the embryos had an embryonic disk — a flat mass of cells. These disks eventually formed the three main cell layers of the body: the endoderm, mesoderm and ectoderm. The lab-grown embryos also showed genetic features similar to those seen in natural monkey embryos within the same time frame.

By day 20, the embryos had developed a neural plate — one of the early hallmarks of the nervous system. As in natural embryos, this plate thickened and bent into a tube that forms the basis of the brain and spine. Wang and her team also pinpointed cells that would eventually become motor neurons. The insights gleaned from the lab-grown embryos will help researchers to develop a better understanding of early embryo development in primates, says Wang.

Where blood is born

In the second study, Tao Tan, a developmental biologist at Kunming University of Science and Technology in Yunnan, China, and his colleagues also generated blastocysts from cynomolgus monkey eggs and sperm. But they used two different types of cell culture to provide stronger mechanical support for the embryos, and added glucose to provide them with energy as they grew.

As in Wang’s study, most of the cells in the cultured monkey embryos were the same type as those typically seen in natural embryos 18 to 25 days after fertilization. When Tan and colleagues took a closer look at the embryos’ mesoderm cells, they found that some had differentiated into heart muscle cells and others had matured into cells found in the lining of blood and lymphatic vessels. The team also pinpointed cells that develop into connective tissue and ones that form the foundation of the digestive system.

Human embryo science: can the world’s regulators keep pace?

The researchers also found signs that blood cells and their components were beginning to take shape in the yolk sac, which supplies embryos with nutrients. “We were deeply impressed,” says Tan. These blood cells “are almost impossible to obtain during human embryonic development.”

Naomi Moris, a developmental biologist at the University of Cambridge, UK, says that the studies present an important step in developing methods that can sustain embryos outside the womb for longer than had been possible previously. But she cautions that there is still a long way to go before lab-grown embryos will look and behave like the real thing. “They still look a bit different to how we would expect [them] to look at these stages,” says Moris, who was not involved in the research. “There’s definitely still scope for improvement.”

article_text: Scientists have cultivated monkey embryos in the laboratory long enough to watch the beginning of organ formation and the development of the nervous system — milestones that are difficult to observe in embryos growing in the uterus. The embryos reached the age of 25 days, making them what might be the oldest primate embryos to be grown outside the womb. Independent teams described the findings in separate papers1,2 in Cell on 11 May. “It’s very impressive,” says Magdalena Zernicka-Goetz, a developmental biologist at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena, who was not involved in the research. “It’s going to bring a lot of new insights.” Few things are as difficult as keeping lab-grown embryos alive for longer than a couple of weeks — most amount to nothing more than a mixed bag of cells in a dish. Previously, both teams had managed to culture monkey blastocysts — balls of dividing cells — in Petri dishes for up to 20 days3,4. Past that point, all the embryos had collapsed, making it impossible to see more advanced stages of their development, such as early signs of the nervous system and organ formation. But in the new studies, the researchers grew monkey embryos in small vials of culture medium, which allowed the embryos to grow in three dimensions as they would inside the womb. Both teams coaxed their embryos to survive for 25 days after fertilization. Neither the authors nor outside scientists contacted by Nature knew of older primate embryos grown in the lab. Hongmei Wang, a developmental biologist at the State Key Laboratory of Stem Cell and Reproductive Biology at the Chinese Academy of Sciences in Beijing, and her team obtained egg cells from female cynomolgus monkeys (Macaca fascicularis) and fertilized them in the lab with sperm collected from their male counterparts. A week later, they placed the resulting blastocysts into a gel-like substance in small cylindrical containers and watched them grow for 25 days.

Stem-cell-derived ‘embryos’ implanted in monkeys

Roughly two weeks after fertilization, more than half of the embryos had an embryonic disk — a flat mass of cells. These disks eventually formed the three main cell layers of the body: the endoderm, mesoderm and ectoderm. The lab-grown embryos also showed genetic features similar to those seen in natural monkey embryos within the same time frame. By day 20, the embryos had developed a neural plate — one of the early hallmarks of the nervous system. As in natural embryos, this plate thickened and bent into a tube that forms the basis of the brain and spine. Wang and her team also pinpointed cells that would eventually become motor neurons. The insights gleaned from the lab-grown embryos will help researchers to develop a better understanding of early embryo development in primates, says Wang. In the second study, Tao Tan, a developmental biologist at Kunming University of Science and Technology in Yunnan, China, and his colleagues also generated blastocysts from cynomolgus monkey eggs and sperm. But they used two different types of cell culture to provide stronger mechanical support for the embryos, and added glucose to provide them with energy as they grew. As in Wang’s study, most of the cells in the cultured monkey embryos were the same type as those typically seen in natural embryos 18 to 25 days after fertilization. When Tan and colleagues took a closer look at the embryos’ mesoderm cells, they found that some had differentiated into heart muscle cells and others had matured into cells found in the lining of blood and lymphatic vessels. The team also pinpointed cells that develop into connective tissue and ones that form the foundation of the digestive system.

Human embryo science: can the world’s regulators keep pace?

The researchers also found signs that blood cells and their components were beginning to take shape in the yolk sac, which supplies embryos with nutrients. “We were deeply impressed,” says Tan. These blood cells “are almost impossible to obtain during human embryonic development.” Naomi Moris, a developmental biologist at the University of Cambridge, UK, says that the studies present an important step in developing methods that can sustain embryos outside the womb for longer than had been possible previously. But she cautions that there is still a long way to go before lab-grown embryos will look and behave like the real thing. “They still look a bit different to how we would expect [them] to look at these stages,” says Moris, who was not involved in the research. “There’s definitely still scope for improvement.” vocabulary:

{'blastocysts': '胚泡,指卵子受精后的第一个发育阶段,由一个细胞层组成,内含一个空泡,空泡内含有胚乳,胚乳可以提供胚胎的营养物质','endoderm': '内胚层,指胚胎发育过程中的第一个胚层,位于胚胎中心,形成胚胎内部的器官','mesoderm': '中胚层,指胚胎发育过程中的第二个胚层,位于内胚层和外胚层之间,形成胚胎的肌肉、血管、骨骼等','ectoderm': '外胚层,指胚胎发育过程中的第三个胚层,位于胚胎外部,形成胚胎的外部特征,如皮肤、毛发、牙齿等','neural plate': '神经板,指胚胎发育过程中的一个重要阶段,形成了大脑和脊髓的基础','yolk sac': '卵黄囊,指胚胎发育过程中的一个重要结构,负责提供胚胎的营养物质','blastocyst': '胚泡,指卵子受精后的第一个发育阶段,由一个细胞层组成,内含一个空泡,空泡内含有胚乳,胚乳可以提供胚胎的营养物质','fertilization': '受精,指卵子和精子结合,形成受精卵的过程','cynomolgus': '猕猴,指一种亚洲猴,体型中等,头部短小,尾巴长而粗,毛色深褐色','gel-like': '凝胶状的,指物质的状态,具有凝胶的特性,可以把物质固定在一起','glucose': '葡萄糖,指一种糖类物质,是最常见的糖类物质,可以提供胚胎的能量','motor neurons': '运动神经元,指一种神经元,负责控制肌肉的收缩,从而实现运动','heart muscle cells': '心肌细胞,指一种细胞,负责心脏的收缩和舒张,从而实现心跳','blood vessels': '血管,指一种管状结构,负责将血液从心脏输送到全身各个部位','connective tissue': '结缔组织,指一种组织,负责连接和支撑身体的其他组织','digestive system': '消化系统,指一种系统,负责将食物消化,从而获取营养物质'} readguide:

{'reading_guide': '科学家们在实验室中培育猴子胚胎,观察器官形成的开始和神经系统的发育,这些在子宫内发育的胚胎中很难观察到。这些胚胎达到25天的年龄,使它们成为可能是外部子宫发育的最老的灵长类胚胎。独立的团队在5月11日的《细胞》杂志上发表了两篇不同的论文。加州理工学院帕萨迪纳的发育生物学家Magdalena Zernicka-Goetz表示:“这非常令人印象深刻,它将带来很多新的见解。”在实验室中培育胚胎活得比几周更久的事情几乎没有,大多数只不过是一碟混合细胞。此前,两个团队都成功地将猴子植入体在培养皿中培养了20天3,4。超过这一点,所有的胚胎都坍塌了,使得无法观察到更高级别的发育,如神经系统和器官形成的早期迹象。但是在新的研究中,研究人员在培养基中培育猴子胚胎,使胚胎能够像子宫内一样以三维形式生长。两个团队都催生了他们的胚胎,使它们在受精后存活25天。作者和Nature联系的外部科学家都不知道在实验室中培育的更老的灵长类胚胎。中国科学院北京干细胞与生殖生物学国家重点实验室的发育生物学家王红梅和她的团队从雌性猕猴(Macaca fascicularis)获得卵细胞,并在实验室用其雄性同伴收集的精子进行受精。一周后,他们将产生的植入体放入小圆柱形容器中的凝胶状物质中,观察它们生长25天。大约受精两周后,超过一半的胚胎有胚盘,这是一团细胞。这些盘子最终形成了身体的三个主要细胞层:内胚层、间胚层和外胚层。实验室培育的胚胎也显示出与同一时间段内自然猴子胚胎中观察到的遗传特征相似的遗传特征。到第20天,胚胎已经形成了神经板——神经系统的早期标志之一。与自然胚胎一样,这个板子变厚并弯曲成一个管,形成大脑和脊椎的基础。王红梅和她的团队还确定了将最终变成运动神经元的细胞。他们的研究将有助于研究人员更好地理解灵长类胚胎早期发育,王红梅说。在第二项研究中,云南昆明科技大学的发育生物学家陶坦和他的同事也从猕猴卵细胞和精子中产生了植入体。但是他们使用了两种不同类型的细胞培养来为胚胎提供更强的机械支持,并加入葡萄糖为它们提供能量以便生长。与王红梅的研究一样,培养的猴子胚胎中的大多数细胞都与受精18到25天后通常观察到的细胞类型相同。当陶坦 long_sentences:

{'sentence 1': 'But in the new studies, the researchers grew monkey embryos in small vials of culture medium, which allowed the embryos to grow in three dimensions as they would inside the womb.', 'sentence 2': 'The lab-grown embryos also showed genetic features similar to those seen in natural monkey embryos within the same time frame.'}

sentence 1:但是在新的研究中,研究人员在小型培养基瓶中培育猴胚胎,这使得胚胎能够像在子宫内一样在三维空间中生长。

句子结构分析:这是一个复合句,主句是“研究人员在小型培养基瓶中培育猴胚胎”,其中“研究人员”是主语,“在小型培养基瓶中培育猴胚胎”是谓语,而“which allowed the embryos to grow in three dimensions as they would inside the womb”是定语从句,修饰“小型培养基瓶”。

语义分析:这句话的意思是,研究人员在小型培养基瓶中培育猴胚胎,这使得胚胎能够像在子宫内一样在三维空间中生长。这句话描述了研究人员在实验室中培育猴胚胎的方法,以及这种方法带来的好处。

sentence 2:实验室培育的猴胚胎也表现出与自然猴胚胎在同一时间框架内相似的基因特征。

句子结构分析:这是一个简单句,主语是“实验室培育的猴胚胎”,谓语是“表现出”,而“与自然猴胚胎在同一时间框架内相似的基因特征”是宾语。

语义分析:这句话的意思是,实验室培育的猴胚胎也表现出与自然猴胚胎在同一时间框架内相似的基因特征。这句话描述了实验室培育的猴胚胎与自然猴胚胎的相似之处,表明实验室培育的猴胚胎可以用来研究自然猴胚胎的发育过程。