- Thu 04 May 2023

- nature

- Alexandra Witze

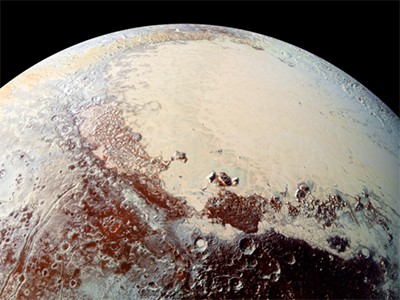

NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft snapped this image of Pluto (lower right) and its moon Charon (upper left) as it passed by in 2015. Credit: NASA/Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory/Southwest Research Institute

In the distant reaches of the Solar System, more than 8 billion kilometres from Earth, NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft is at the centre of a dispute over its future.

Pluto’s geology is unlike any other

The craft, which snapped stunning images during humanity’s first visit to Pluto in 2015 , is within a few years of exiting the Kuiper belt, the realm of frozen objects that orbit the Sun beyond Neptune. In addition to Pluto, it has flown past another Kuiper belt object called Arrokoth, but has not found a third object to visit before it leaves. So NASA now plans to repurpose the spacecraft mainly as a heliophysics mission, to study space weather and other phenomena that it can measure from its unique location in the Solar System.

But some are unhappy with the decision, and worry that planetary studies are being truncated too soon. “Scientifically, I just don’t feel that we’re at diminishing returns yet,” says Kelsi Singer, the mission’s project scientist at the Southwest Research Institute in Boulder, Colorado.

Shifting New Horizons from being a planetary explorer to an interstellar emissary echoes what the agency did with the twin Voyager spacecraft after they visited the outer planets in the 1980s. “We have this perfectly working spacecraft that’s in a unique area,” says Nicola Fox, head of NASA’s science mission directorate in Washington DC. The agency wants to get the “best use” out of it, she says, as well as “open it up to as many scientists from as many disciplines as are interested”.

A mission takeover?

No one disputes that New Horizons has made stunning discoveries in the Kuiper belt, which contains debris left over from the Solar System’s early history. The spacecraft has uncovered secrets of Pluto’s icy surface and revealed more about how the building blocks of planets might have come together. Its 2019 fly-by of Arrokoth , a 35-kilometre-long Kuiper belt object made of two chunks of stuck-together space rock, “taught us so much about fundamental properties of planetary formation — completely transformational”, says Michele Bannister, a planetary scientist at the University of Canterbury in Christchurch, New Zealand.

New Horizons visited the Kuiper belt object Arrokoth in 2019. Credit: NASA/Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory/Southwest Research Institute/Roman Tkachenko

Without another Kuiper belt object to fly by, the planetary science for New Horizons becomes harder to justify, some say. Tensions arose last year after NASA’s planetary science division conducted a ‘senior review’ of its operational missions, as it does every few years. A panel of scientists evaluated eight missions, including New Horizons, for their recent scientific performance and future promise.

That review rated New Horizons’ current science as “excellent/very good” if planetary science, astrophysics and heliophysics were all included. The rating slid to “very good/good” for planetary science alone, in part because the science team’s proposed studies of Kuiper belt objects were “unlikely to dramatically improve the state of knowledge”, the review said. (The mission’s science team disputes that conclusion.)

NASA used the review in its decision to shift the spacecraft to being managed as a heliophysics mission, says Lori Glaze, head of the agency’s planetary science division. “Because that’s where the strength lies — in the science that can be conducted from here forward,” she says.

Solar System’s distant snowman comes into sharp focus

NASA will fund the mission from its planetary science budget until 30 September 2024. After that, management could be taken over by the much smaller heliophysics division, potentially involving a new group of scientists. In March, NASA asked US researchers for ideas on what science New Horizons could do across all disciplines, “to gauge the level of interest of the wider science community in pursuing the next phase of science leadership for the mission, and to estimate appropriate annual costs”.

To the mission’s current science team, this amounts to a takeover. “There’s going to be a boarding party on the first of October next year,” says Alan Stern, the mission’s principal investigator, who is also at the Southwest Research Institute. Fox responds that the New Horizons team was invited to submit a proposal to lead the spacecraft’s science in the heliophysics division starting in October 2024, and that the researchers declined.

Full replacement of a mission’s science team is relatively rare, says Amanda Hendrix, a researcher at the Planetary Science Institute in Boulder, Colorado. “This is kind of new territory that we’re getting into.”

In a ‘unique position’

Now the question is what science can still be done with New Horizons, and how. Although its plutonium power source is waning with time, it has enough to last probably another quarter of a century.

The craft is currently in the outer part of the Kuiper belt (see ‘Out there’), about which little is known because it can’t be observed well from Earth. “New Horizons is in a very unique position, and there’s basically no other way to get this information,” Singer says.

Source: NASA/Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory/Southwest Research Institute

Among other studies, New Horizons has been taking repeated pictures of distant Kuiper belt objects, building up information on their shapes and surface properties. The spacecraft also analyses dust in the Kuiper belt — data that can shed light on how often space rocks smash into each other.

In recent years, the spacecraft has begun to broaden its focus. In astrophysics, New Horizons’ location allows it to study several types of background light that permeate the Solar System. And in heliophysics, ongoing and future studies are exploring the floods of charged particles emanating from the Sun. “It’s very valuable in conjunction with the two Voyagers,” says Stamatios Krimigis, a space physicist and the only scientist who has been involved with missions to all of the Solar System’s planets and Pluto.

New Horizons, which cost US$780 million to build, launch and fly past Pluto, currently costs NASA around $10 million annually. Both Fox and Glaze told Nature that the decision to shift the mission away from planetary science was not driven by budgetary issues, such as those that have delayed a Venus mission and raised concerns over the cost of Mars sample return .

Both also said that if a Kuiper belt object were found that New Horizons could reach, NASA would be open to discussing that, even if the mission had already been shifted to heliophysics. Stern and his team continue to look for a fly-by target in the time they have left.

article_text: In the distant reaches of the Solar System, more than 8 billion kilometres from Earth, NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft is at the centre of a dispute over its future.

Pluto’s geology is unlike any other

The craft, which snapped stunning images during humanity’s first visit to Pluto in 2015, is within a few years of exiting the Kuiper belt, the realm of frozen objects that orbit the Sun beyond Neptune. In addition to Pluto, it has flown past another Kuiper belt object called Arrokoth, but has not found a third object to visit before it leaves. So NASA now plans to repurpose the spacecraft mainly as a heliophysics mission, to study space weather and other phenomena that it can measure from its unique location in the Solar System. But some are unhappy with the decision, and worry that planetary studies are being truncated too soon. “Scientifically, I just don’t feel that we’re at diminishing returns yet,” says Kelsi Singer, the mission’s project scientist at the Southwest Research Institute in Boulder, Colorado. Shifting New Horizons from being a planetary explorer to an interstellar emissary echoes what the agency did with the twin Voyager spacecraft after they visited the outer planets in the 1980s. “We have this perfectly working spacecraft that’s in a unique area,” says Nicola Fox, head of NASA’s science mission directorate in Washington DC. The agency wants to get the “best use” out of it, she says, as well as “open it up to as many scientists from as many disciplines as are interested”. No one disputes that New Horizons has made stunning discoveries in the Kuiper belt, which contains debris left over from the Solar System’s early history. The spacecraft has uncovered secrets of Pluto’s icy surface and revealed more about how the building blocks of planets might have come together. Its 2019 fly-by of Arrokoth, a 35-kilometre-long Kuiper belt object made of two chunks of stuck-together space rock, “taught us so much about fundamental properties of planetary formation — completely transformational”, says Michele Bannister, a planetary scientist at the University of Canterbury in Christchurch, New Zealand. Without another Kuiper belt object to fly by, the planetary science for New Horizons becomes harder to justify, some say. Tensions arose last year after NASA’s planetary science division conducted a ‘senior review’ of its operational missions, as it does every few years. A panel of scientists evaluated eight missions, including New Horizons, for their recent scientific performance and future promise. That review rated New Horizons’ current science as “excellent/very good” if planetary science, astrophysics and heliophysics were all included. The rating slid to “very good/good” for planetary science alone, in part because the science team’s proposed studies of Kuiper belt objects were “unlikely to dramatically improve the state of knowledge”, the review said. (The mission’s science team disputes that conclusion.) NASA used the review in its decision to shift the spacecraft to being managed as a heliophysics mission, says Lori Glaze, head of the agency’s planetary science division. “Because that’s where the strength lies — in the science that can be conducted from here forward,” she says.

Solar System’s distant snowman comes into sharp focus

NASA will fund the mission from its planetary science budget until 30 September 2024. After that, management could be taken over by the much smaller heliophysics division, potentially involving a new group of scientists. In March, NASA asked US researchers for ideas on what science New Horizons could do across all disciplines, “to gauge the level of interest of the wider science community in pursuing the next phase of science leadership for the mission, and to estimate appropriate annual costs”. To the mission’s current science team, this amounts to a takeover. “There’s going to be a boarding party on the first of October next year,” says Alan Stern, the mission’s principal investigator, who is also at the Southwest Research Institute. Fox responds that the New Horizons team was invited to submit a proposal to lead the spacecraft’s science in the heliophysics division starting in October 2024, and that the researchers declined. Full replacement of a mission’s science team is relatively rare, says Amanda Hendrix, a researcher at the Planetary Science Institute in Boulder, Colorado. “This is kind of new territory that we’re getting into.” Now the question is what science can still be done with New Horizons, and how. Although its plutonium power source is waning with time, it has enough to last probably another quarter of a century. The craft is currently in the outer part of the Kuiper belt (see ‘Out there’), about which little is known because it can’t be observed well from Earth. “New Horizons is in a very unique position, and there’s basically no other way to get this information,” Singer says. Among other studies, New Horizons has been taking repeated pictures of distant Kuiper belt objects, building up information on their shapes and surface properties. The spacecraft also analyses dust in the Kuiper belt — data that can shed light on how often space rocks smash into each other. In recent years, the spacecraft has begun to broaden its focus. In astrophysics, New Horizons’ location allows it to study several types of background light that permeate the Solar System. And in heliophysics, ongoing and future studies are exploring the floods of charged particles emanating from the Sun. “It’s very valuable in conjunction with the two Voyagers,” says Stamatios Krimigis, a space physicist and the only scientist who has been involved with missions to all of the Solar System’s planets and Pluto. New Horizons, which cost US$780 million to build, launch and fly past Pluto, currently costs NASA around $10 million annually. Both Fox and Glaze told Nature that the decision to shift the mission away from planetary science was not driven by budgetary issues, such as those that have delayed a Venus mission and raised concerns over the cost of Mars sample return. Both also said that if a Kuiper belt object were found that New Horizons could reach, NASA would be open to discussing that, even if the mission had already been shifted to heliophysics. Stern and his team continue to look for a fly-by target in the time they have left. vocabulary:

{'Heliophysics': '太阳物理学,是研究太阳及其环境的科学,包括太阳磁场、太阳风、太阳射线、太阳活动等','Kuiper belt': '库伊珀带,是太阳系外层的一个冰封的小行星带,位于海王星以外,由冰块、小行星和小行星残骸组成','Arrokoth': '阿罗科斯,是库伊珀带中的一颗小行星,由两个粒子组成,位于海王星以外','Senor review': '高级评审,是指每隔几年,NASA的行星科学部门对八个任务进行评估,以评估这些任务的最近科学表现和未来前景','Interstellar': '星际,指的是星系之间的空间','Emissary': '使者,指的是派遣的代表','Voyager': '旅行者,指的是美国宇航局发射的探测器','Plutonium': '钚,指的是一种放射性元素','Astrophysics': '天体物理学,是研究宇宙中的物质、能量和空间的科学','Stagnant': '停滞的,指的是没有变化的','Transformational': '变革性的,指的是有着重大影响的','Diminishing': '减少的,指的是变少的','Proposed': '提议的,指的是提出的','Appropriate': '适当的,指的是合适的','Permeate': '渗透,指的是渗入','Emanating': '散发,指的是发出','Waning': '减弱,指的是变弱','Boarded': '登船,指的是上船','Replacement': '替换,指的是替换','Smash': '砸,指的是砸碎'} readguide:

{'reading_guide': '本文讲述了美国宇航局新视野号探测器在太阳系最远处的情况,它曾经拍摄了普鲁托行星的惊人照片,现在它即将离开太阳系,NASA计划将其重新定位为太阳物理学任务,以研究太空天气和其他太阳系特有的现象。但有些人对这一决定不满,担心行星研究过早终止。文章还提到,新视野号可以继续进行太阳物理学、天体物理学和行星物理学研究,以及探索太阳系边缘的尘埃等。'} long_sentences:

{'sentence 1': 'NASA now plans to repurpose the spacecraft mainly as a heliophysics mission, to study space weather and other phenomena that it can measure from its unique location in the Solar System.', 'sentence 2': 'In recent years, the spacecraft has begun to broaden its focus. In astrophysics, New Horizons’ location allows it to study several types of background light that permeate the Solar System. And in heliophysics, ongoing and future studies are exploring the floods of charged particles emanating from the Sun.'}

Sentence 1: NASA现在计划将飞船主要用作太阳物理学任务,以研究它可以从太阳系独特的位置测量的太空天气和其他现象。句子结构:主语是NASA,谓语是plans,宾语是the spacecraft,定语从句修饰宾语,表示目的状语从句修饰谓语,表示目的。句子语义:NASA计划将飞船用作太阳物理学任务,以研究它可以从太阳系独特的位置测量的太空天气和其他现象。

Sentence 2: 近年来,飞船开始扩大其聚焦范围。在天体物理学中,新视野的位置使它能够研究太阳系中渗透的几种背景光。而在太阳物理学中,正在进行的和未来的研究正在探索太阳发出的带电粒子洪流。句子结构:主语是the spacecraft,谓语是has begun,宾语是to broaden its focus,定语从句修饰宾语,表示范围,两个并列的状语从句修饰谓语,表示范围。句子语义:飞船开始扩大其聚焦范围,在天体物理学中,新视野的位置使它能够研究太阳系中渗透的几种背景光,而在太阳物理学中,正在进行的和未来的研究正在探索太阳发出的带电粒子洪流。